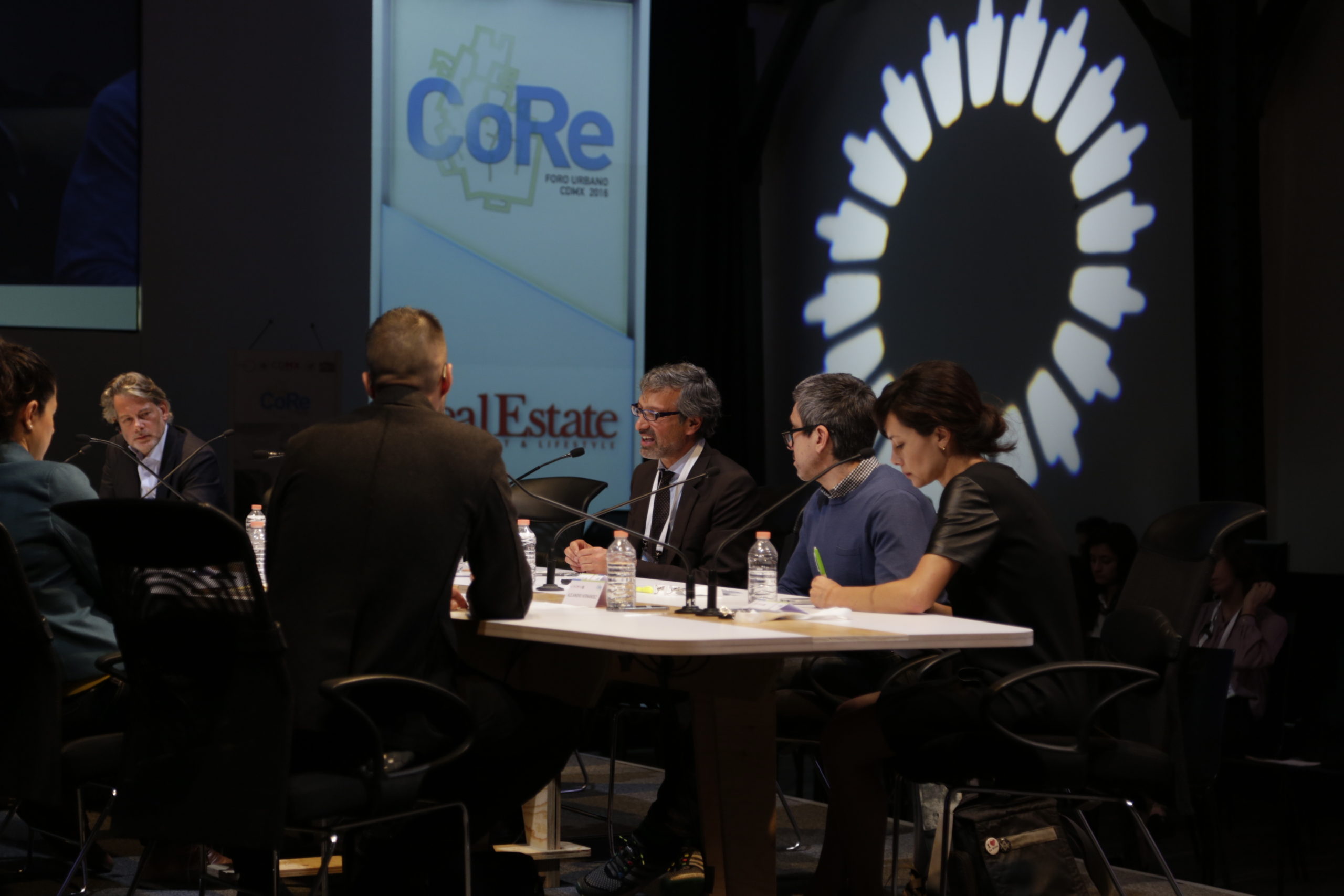

Citizen participation must be seen as a toolbox to build public space: Roundtable on participation, citizenship and responsibility

- “Citizen participation is key to generating empathy. Social conversation and a level of horizontal citizenship should be encouraged “: Steven Popper.

- “The 3×3 law has brought about fundamental changes, perhaps the most important of which is that corruption is being pursued ex officio. These changes are incentives to modify the political system in such a way that corruption no longer has a place in Mexican politics”: Juan Pardinas.

Mexico City, December 7, 2016.- Citizen participation and responsibility was the theme of the fourth and final roundtable of the CoRe Foro Urbano CDMX 2016, presented by Steven Popper, senior economist at the RAND Corporation and the General Director of the Mexican Institute of Competitiveness (IMCO), Juan Pardinas.

The opening speech was delivered by Gabriela Alarcón, Director of Urban Development at IMCO, who said that the extent of citizen participation should be better defined within the redesign of cities in order to understand its limits and how to best rebuild trust among the public.

For Popper, the fundamental question is how to support a process of citizen participation and collaboration. “A process of urban value and innovation usually follows this order: research, development, invention, adoption and dissemination. But it’s not always like this. I would say that it is particularly difficult in Mexico City, where the problem is that the participants are not connected. Entrepreneurs, academics, workers, students and others do not have a linear communication where they share concerns or risks. Trust is strictly related to risk. In Mexico City, risk is not shared horizontally. ”

For Popper, there are three causes of mistrust that prevent the construction of citizenship in Mexico: first, the coexistence of many people with different objectives, interests and fears, which can be a breeding ground for corruption; second, not understanding that the urban planning process is more important than the final product; and third, uncertainty, which is a risk without calculation.

“One of the problems is the privatization of interests. The explicit declaration of an urban vision is too important to be left to the ordinary visionaries on these issues, such as architects or urban developers. Citizen participation is key to generating empathy. Social conversation and a level of horizontal citizenship should be encouraged”, he pointed out.

In his intervention, Juan Pardinas considered that the construction of citizenship is vital and has to be dynamic: “Citizenship must be seen as a toolbox that will serve to build up public spaces, including the votes from women and the opinions of marginal or minority communities.”

Pardinas also made a counterpoint to the causes of distrust raised by Popper. Before 2014, the only people in the country with the power to initiate laws were the President and members of Congress. This changed with the 2014 Reform, allowing Mexicans to participate in the construction of laws. “The 3×3 Law has brought about fundamental changes, perhaps the most important of which is that corruption is being pursued ex officio. These changes are incentives to change the political system in such a way that corruption no longer has a place in Mexican politics. ”

For Pardinas, current technology, such as the connectivity provided by a smartphone, is a great tool for building up citizenship and trust in that process. However, they can also present threats that must be analyzed. In his opinion, citizens belong to the city, an image Pardinas encapsulated with a sentence from the Citizen Manifesto: I prefer cities to nations.

In her participation, Ana Ramírez Lacorte mentioned that “although there is an empowered community in Mexico City that has achieved great results such as the rededication of the Chapultepec Corridor, there are still many neighborhood organizations that require attention.”

These words triggered the discussion regarding one of Mexico City’s most persistent problems: inequality.

Alejandro Hernández proposed a dilemma: how to encourage citizen participation, especially on urban issues, when many of them survive on a salary of less than 7,000 pesos per month?

In this regard, María Amparo Casar added that “Mexico generally has low-intensity citizens, but we must recognize the causes of this low citizen participation. According to the surveys, very little progress has been made in terms of the rule of law since the 1950s. Surveys say that only 3 to 10 percent of Mexicans have participated in any activity of social manifestation, and most of those that have do so within a church setting. Statistics also reveal that Mexicans do not participate because of a lack of confidence and because they feel that participating, makes no difference,” she pointed out.

Part of the eradication of inequality, at least in terms of citizen participation, has to involve tolerance, according to Javier Esquillor, who first stated that spaces of recognition should be generated among different population groups. Tolerance in different directions is also a key factor in building citizenship inherent in building trust.

For Jesús “Chuy” Álvarez, from Monterrey, tolerance is built by people getting to know their neighbors and getting involved in the community. One option to help this is to break the verticality within the designs of citizen participation projects. Instead, he called for the value of time to be raised and to make neighbors feel that they are part of an important project.